Life in the 'Dead Zoo'

The Irish Times, Thursday, October 4, 2007

Rosita Boland

Envelopes filled with feathers, and portraits of stuffed animals: an unusual show explores the curious world of the Museum of Natural History, writes Rosita Boland.

Unless you are a scientist or are in possession of good general knowledge, you might be a little bewildered by the elaborate title of artist Karl Grimes's remarkable new exhibition, which is on show at both the National Museum on Kildare Street and at the Gallery of Photography in Temple Bar.

Dignified Kings Play Chess on Fine Green Silk is a mnemonic, used to remind students of the Linnaean Taxonomic Order: a method of classifying living things as originally defined by the famous Swedish botanist and zoologist Carl Linnaeus. Grimes chose it as the title for his new exhibition because of its relevance to the work in his shows - for most of the last year, he has been artist-in-residence at Dublin's Museum of Natural History, a residency that ended prematurely in July with the collapse of a stone staircase and the subsequent temporary closure of the museum.

So how does one work as an artist-in-residence in a place where everything is inanimate? What do you engage with, in the process of creating something new?

The museum has a vast quantity of items in storage, along with an extensive paper archive, much of which relates to the provenance of the exhibits. It was these items, most of which the public would not be aware of, that Grimes spent the most time examining. Some material is held on-site, but the vast majority is stored at an old barracks in Beggars Bush.

"I spent a lot of time just looking. Right until I left, I was still opening boxes," Grimes says. It was like rooting through some great-aunt's attic of curiosities, looking at all these donations and treasures. A museum is always about the process of collecting, classifying and ordering exhibits, and I wanted to look behind the scenes."

There are two complementary parts to Dignified Kings. At Kildare Street, large portrait photographs of various stuffed animals and birds from the museum's collection are displayed on an upper floor. They have an eerie grandeur to them, these haunting formal portraits of dead creatures, prints on silicon, the only clue to their usual location being the museum's light-box atrium, which is reflected in their glass eyes.

"Dubliners were always stealing the eyes of the exhibits," Grimes says. "Not the exhibits themselves, just the eyes," This theft seems somehow surreally appropriate: in death, eyes are always in danger of being pecked out by predators.

The main part of Dignified Kings is at the Gallery of Photography in Dublin's Temple Bar, where the exhibition space is perfectly suited to the show's cabinet-of-curios format. A rich mixture of texts, objects, soundscapes, photographs and drawings makes Grimes' exhibition at least as rewarding, enriching and esoteric as a visit to the famous "Dead Zoo" itself.

THE KEY PART of the exhibition is the fascinating Killed Striking series. Particularly observant visitors to the Museum of Natural History might have noticed that there are only a few cabinets painted white: the "bird wall". These contain birds that were collected by the 19th-century naturalist R. M Barrington, whose obsession was the migratory patterns of birds, then still quite a mysterious act of regular disappearance.

In his attempts to understand more about migration, Barrington wrote to the keepers at every lighthouse and lightship around Ireland, asking for their assistance. Birds that migrate at night are fatally attracted to light, and keepers often found dead bodies scattered around the lighthouses in a halo of feathers each morning. Barrington asked if they would remove a wing and claw from each dead bird they found, log some specific data, and then send them to him in Wicklow, with the promise that postage would be refunded.

Between 1882 and 1900, when Barrington carried out this project, small packages of feathers and claws, along with those containing entire birds that had been stunned to death, started their own migration patterns, arriving with regularity to his home in Wicklow One can only imagine what his postman made of these deliveries. The data Barrington collected formed the basis for his book. Migration of Birds as Observed at Irish Lighthouses and Lightships. He also had his own personal collection of mounted dead birds, many of which are now behind the white cabinets in the Museum of Natural History.

Barrington started this project in 1882, and ended it in 1900. Until 1926, a full 44 years after he had formally ended the project, and 11 years after Barrington's death, bird parts continued to arrive at the Wicklow house from the lighthouses and lightships around Ireland. In 1916, his family donated his entire archive to the Museum of Natural History, and when Grimes went through it, he found the central idea that would ignite his show.

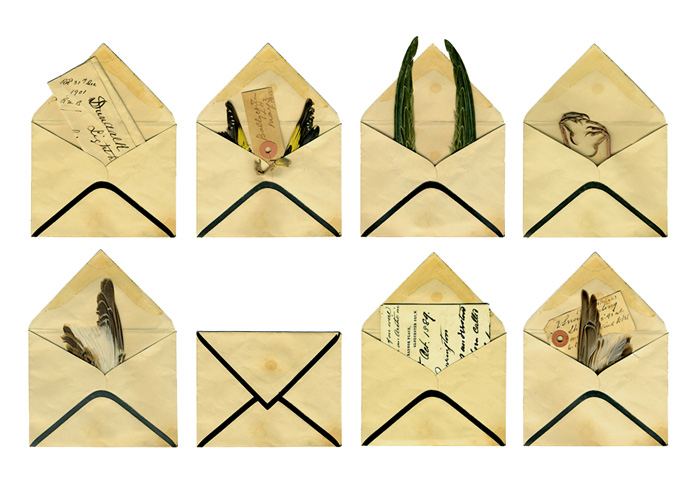

Grimes has photographed some of the original envelopes Barrington was sent, and the series in the gallery, arranged in a large grid, shows glimpses of labels, letters from lighthouse keepers, feathers, claws, all emerging from these envelopes.

An accompanying soundscape in a sidegallery plays the sounds of waves hitting a lighthouse, with a voice-over incanting Barrington's instructions to his willing keepers: "Rare or strange birds should be sent entire." There is a tiny photograph of Barrington himself, in a jewel like frame. It's a compelling and haunting series of installations.

THERE ARE OTHER components to the exhibition, all of them also focused on the theme of collecting, and how collections are ordered. They range from marvelously odd photographs of the plastic dinosaurs and wolves sold in the museum's shop to a series of photographs of masks accompanied by jaw-dropping archival Victorian texts on the methodology of collecting.

The cumulative effect of Dignified Kings is quite wonderful, and has the instant effect of making you want to go straight back to the Museum of Natural History and look at it again through fresh eyes. Sadly, the museum remains closed for the present, but anyone having withdrawal symptoms or wanting to see what its hidden secrets have inspired should go and see this show.

Rosita Boland. The Irish Times, Thursday, October 4, 2007

BACK TO TOP

|

KARL GRIMES - DIGNIFIED KINGS PLAY CHESS ON FINE GREEN SILK

CIRCA, 122 - WINTER 2007

Sherra Murphy

Natural history can be a well constructed language only if the amount of play in it is enclosed: if its descriptive exactitude makes every proposition into an invariable pattern of reality and if the designation or each being indicates clearly the place it occupies in the general arrangement of the whole.(1)

Taxonomies are philosophically risky propositions. Their systemic specificities must, by dint of task, impose an order that can only seem stultifying by comparison to the rude, unruly profusion of the natural world. Tension between the classifying grid of natural history and its irrepressibly prolific subject is the exploratory domain of photographer Karl Grimes's most recent work, installed simultaneously at the Gallery of Photography, Temple Bar, and the National Museum, Kildare Street. In Dignified Kings Play Chess On Fine Green Silk,(2) Grimes trains his compassionate and thoughtful eye on the idiosyncrasies of Dublin's Natural History Museum, where he spent a year as artist-in-residence.

Privileging the image (as opposed to Foucault's textual focus) in his reading of natural history, he demonstrates that the 'descriptive exactitude' of the photograph, rather than underpinning the taxonomic system, may well undermine it. Invoking the careful observation beloved of Victorian science, Grimes intimates that its subjects stubbornly resist the neat categorisations required by the Linnaean system.

Grids recur regularly in Grimes's work, here shaping a framework entirely consistent with the subject matter. Killed Striking I is an engagement with the Barrington bird collection, a compulsive assembly of Ireland's aves, laid out in white boxes across the Museum's walls. In his quest to discover information about migratory patterns, R.M Barrington developed a network of light keepers, who posted him the wings and legs of birds which had died flying into lighthouses, blinded by the beams, often during storms.

The Museum still holds this collection of migratory fragments and their accompanying documents; Grimes depicts it in a grid of 39 photographs, each one comprising a square black-bordered envelope, divulging or obscuring its contents. The rhythms of wings and legs emerging from some of the regularised black and sepia squares counterpoint the paperwork and identification tags peeping from others, or the blank, refusing emptiness of still others. The trompe l'oeil quality of the pigment prints suggests sepia photographs, watercolours and gravures simultaneously, implying an eerie sense that one could pick up and handle the notes, invoices and disembodied limbs, such is their inferred physicality. The specificity of gesture, colour and texture in the animal remains sets them at organic odds with the rigid sameness of Barrington's civilised envelopes; they flutter, arc, struggle to escape the language and geometry binding them. The avian fragments resist their placement in the 'arrangement of the whole', pointing back to their origins, piercing the grid's order. Composed within a phalanx of white frames, their animation defies the intent of the collector to still and classify; they refuse to take their places in the 'boxed set'.

Though the mammal specimens in the Museum are intended as proxies for their live kin, they are in fact reifications - what designates one species from another has largely been removed; the anatomy of bones, organs, musculature, We are left with what amounts to shaped furs, skins with artificial colouring and glass eyes, sculpted into forms saying more about animals-as-idea than conveying anything fundamental about their morphological states.

The Sartorial Taxa and Taxum Totem series describe the artificiality at the heart of the stuffed specimens, invoking tailoring and ritual as apt descriptive frameworks. If natural history as a language or grammar means that each animal must articulate an aspect of the complete grid, become a generality, then Grimes's rendering of individuals elides that ideal - the portrait format distils the reconstructed features, the stitching of the skin, the paint and shiny eyes, into a question about the efficacy of systems employing individuals for describing abstracted totalities. This is further complicated by idiosyncrasy, history and presentation; the taxidermy is old, lumpy and odd. The drop-dead gorgeous images, with rich black grounds and subjects lit as though glowing from the inside, detail scars, bumps, hair and feathers with astonishing tactility. Material attention to specific attributes again foregrounds the visual over the textual, sympathy over nomenclature.

Other classificatory structures are treated in the exhibition; plastic wildlife toys, Victorian instruction manuals, the formal consonance between internal and external architectures. Grimes has skillfully engaged a complex set of historical and contemporary issues surrounding display and classification, the ways we internalise their logic and implications, injecting new visual life into the worn skin of the archive.

1. Michel Foucault, from ‘Classifying', in The Order of things, Routledge, 2001

2. A mnemonic device for the Linnaean taxonomic system - Domain, Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order,Family, Genus, Species

Sherra Murphy. Circa 122. Winter 2007

BACK TO TOP

Archival Mania

SOURCE - WINTER 2007/ISSUE 53

Colin Graham

Karl Grimes, Gallery of Photography and National Museum of Ireland

'Dignified Kings Play Chess On Fine Green Silk' is a mnemonic phrase based on the Linnean system (Domain, Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species). With a sympathetic eye, Karl Grimes' exhibition plays on the pathos and ambition of the kind of archival mania which inspired Victorian naturalists and cataloguers. The exhibition is based around the collection of stuffed and modelled animals in Dublin's Natural History Museum (The Dead Zoo, as it's known), a collection begun in the eighteenth century, shaped into a specific museum in the nineteenth century, and preserved today in its own building as a museum of a museum, retaining its Victorian architecture and its sense of the scientific order which could be given to nature's multiplicity. The Natural History Museum is a testament to the brutal tenderness of Victorian collectors and the ways in which their imperial times animated a quest both for universal knowledge and for a culturally specific natural history of Ireland. Grimes' photographs circulate around these obsessions and histories, allowing for the interplay of stasis and motion, human and animal, which taxidermy in particular invokes to the contemporary eye.

The photographing of museum collections has a long history. Since Roger Fenton's work in the British Museum, photography has had a place, superficially at least, as a kind of insurance policy for collections, a further way of cataloguing the already museumified and supplementing science with an aesthetic and didactic way of looking at the worlds museums encapsulate. Grimes' Dignified Kings makes the most of the visual crossing points at which photography echoes or imitates the museum. In his Taxum Totem series the photographic act becomes analogous to the work of both taxidermist and taxonomist.

Monkeys 'pose' as if instructed by a Victorian studio portrait photographer, their far-away gaze eerily replicating that of the adventurers who captured them, killed them and had them stuffed. Equally in several of the groupings in the Taxum images there are reminders of photography's role in nineteenth-century ethnography as animals are posed in supposedly typical ways, revealing their place in the order of things, much as 'tribal' life was reconstructed in the photographic anthropology of the nineteenth century.

Grimes' vision is not, however, trammelled by the dead hand of history hanging over the Dead Zoo. As with his previous projects, his images toy with a ghostly animation that seems to emanate from the objects he photographs. There are a series of photographs of surreal animal facial expressions, all anthropomorphic in themselves but made even more so by Grimes' imitation of serious portraiture. A few exorbitant arrangements of fur (in Taxum Totem 017-021) are found in the gathering of a wild cat, two small monkeys and a large rodent, forming a quartet which has the look of a set of portraits from an underworld gentleman's club of the eighteenth century.

Central to the story of the Natural History Museum is the sometimes eccentric naturalist R.M. Barrington, One of Barrington’s most innovative ideas was to ask the lighthouse keepers of Ireland to send him the legs and wings of birds which had died by flying into the lighthouses. From this unlikely project Barrington was able to gather a large enough set of specimens to write an early study of the migration patterns of birds in and across Ireland. Grimes shows us some of the letters sent to Barrington by the lighthouse men, or at least the envelopes with wings or gnarled legs jutting out of them. Each yellowed envelope has a black border in the manner of Victorian stationery used for writing sympathy letters after a death. This gentle recognition of humour, sympathy and idiosyncracy are central to Grimes' way of seeing museum culture. Also in this vein are the images which look out across the sea-views from Rockabill and Tusker lighthouses (in light box transparencies), creating seascapes which certainly give an apparitional aesthetic to the memories of both the lighthouse keepers and the dead birds of Barrington's past, but which photographically are perhaps too close to the seascapes of Hiroshi Sugimoto to be coherently integrated into the exhibition.

Dignified Kings, is replete with the false eyes of stuffed animals looking into the unfathomable. As the rows of antelope heads stare at each other across the higher levels of the Natural History Museum there is both a dark comedy to their appearance and a hint, which Grimes makes by turns comic and thoughtful, that they can remember something beyond the confines of the museum which holds them. Just as the Linnean system, which is everywhere evident in the very fabric and structure of the museum, struggles to cope with the variety and strangeness of the natural world (there is one image of exhibits on the 'Not Named' shelf), so the images in Dignified Kings revel in the weirdness of nature in a glass case, and configure the glass as a mirror to the human. Grimes sees the museum space as one that contains, but also one that inevitably spills out beyond its own boundaries - into store rooms and corridors but also into details, incongruities and the suggestions of nearly forgotten stories.

Colin Graham

SOURCE - WINTER 2007/ISSUE 53

BACK TO TOP

|

|